Papert’s theory of constructionism is based on the theoretical basis for making, which is a stance toward learning that is predicated on the active construction of a shareable artefact. Not to be confused with the linguistically similar theory of constructivism, the theory of constructionism sees leaners move from passive receivers of knowledge, to real world makers and promotes creativity, tinkering, exploring, building and presentation in the learning process (Martinez & Stager 2014, Donaldson 2014). To bring this theory to life in the classroom, teachers can integrate a makerspace into their classroom. Sheridan et al (2014) describe makerspaces as “informal sites for creative production in art, science, and engineering where people of all ages blend digital and physical technologies to explore ideas, learn technical skills and create new products”. These spaces are particularly useful for STEM subjects and allow for students to work with their hands and create something via woodworking, metalworking, robotics and a number of other methods.

Donaldson (2014) highlights the fact that the creations born from a makerspace do not necessarily have to be a physical objects. Published digital portfolios are one example of a non-physical creation, where students upload their digital creations and explain to the reader their thought process behind the creation. This allows for deeper understanding of the learning material, strengthening of student metacognitive processes, and opportunities for students to give feedback to one another.

Makers Empire

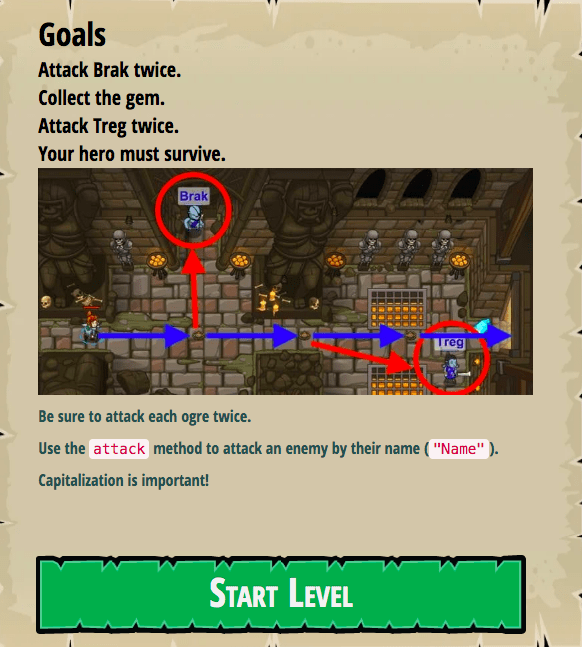

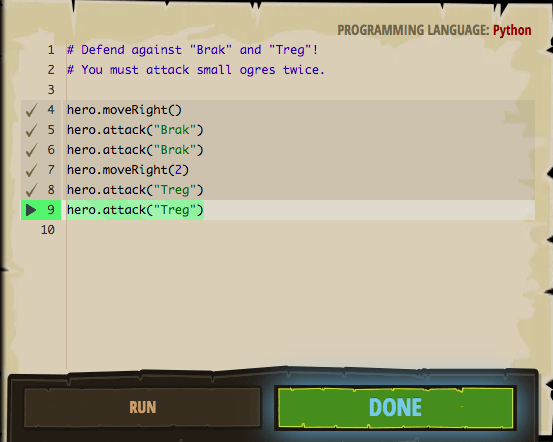

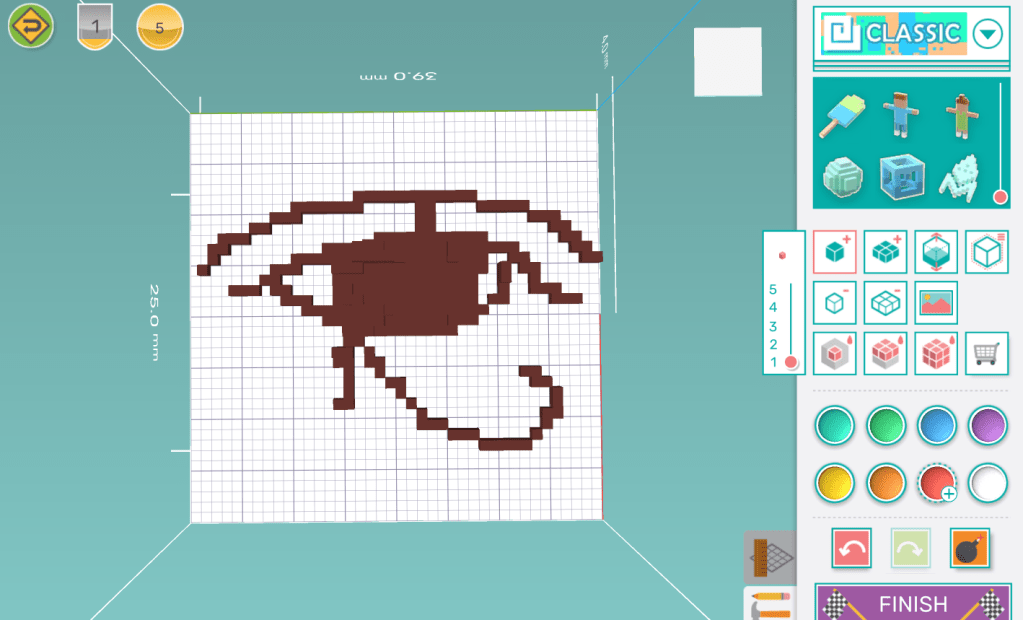

Makers Empire is a 3D design tool that educators can use in their maker spaces. This tool allows students to design objects in 3D that can then be printed using a 3D printer. This technology is effective in helping develop STEM, design thinking and 21st century capabilities for K-8 students (Bower et al 2018). It is accessible on computers, tablets and phones.

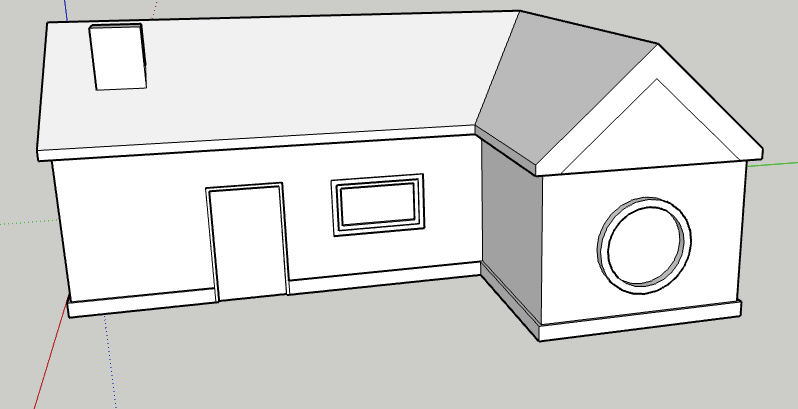

Whilst particularly useful in STEM subjects, Makers Empire can still lend itself to other subjects, such as history, and foster student creativity. For example, students can use Makers Empire to help recreate ancient artefacts and symbols that can then be printed and examined by the student. An example 3D designed artefact is pictured below. Whilst Makers Empire creates a number of opportunities for learning in the K-8 range, its uses become limited when being used for upper secondary students.

References:

- Bower, M., Stevenson, M., Falloon, G., Forbes, A., & Hatzigianni, M. (2018). Makerspaces in primary school settings: advancing 21st century and STEM capabilities using 3D design and printing.

- Donaldson, J. (2014). The Maker Movement and the rebirth of Constructionism. Hybrid Pedagogy.

- Martinez, S., & Stager, G. (2014). The maker movement: A learning revolution. Learning & Leading with Technology

- Sheridan, K., Halverson, E., Litts, B., Brahms, L., Jacobs-Priebe, L., & Owens, T. (2014). Learning in the Making: A Comparative Case Study of Three Makerspaces. Harvard Educational Review, 84(4), 505-531.